Early Automobiles and “Separate Spheres”

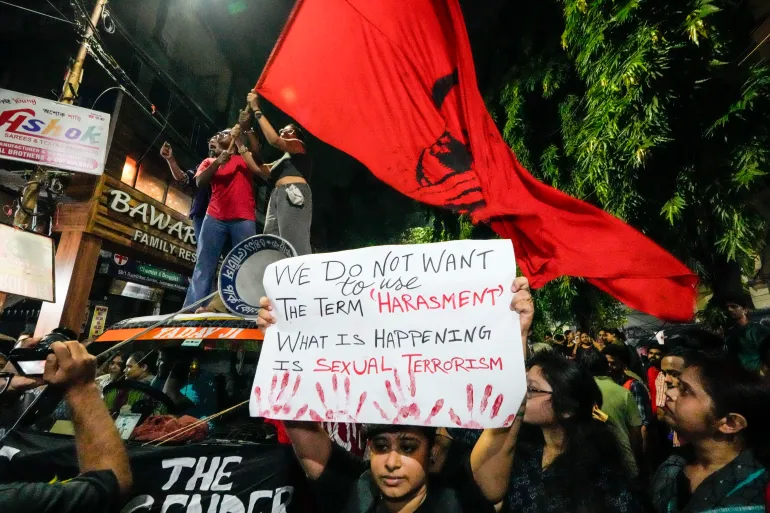

During the nineteenth century, various experts—doctors, professors, ministers, politicians—conceived of the American lady as frail, timid, easily shocked, and quickly exhausted, physically and temperamentally incapable of mastering the demands of public life. Born to the weak sex, biology consigned her to lifelong inactivity and immobility. Prominent men thus registered their fears about the consequences of women’s emergence from the private world of home into the public realm. They worried that women would neglect their housekeeping, ignore their children, undermine proper relations between the classes and races, and degrade their morals if involved in public life. Invoking the fragility of women’s bodies, the feebleness of their brains, or the frailty of their characters, Victorian experts admonished women to stay at home. Women could only dirty themselves, they argued, by venturing beyond the front door, into the hectic and unpredictable crush of public traffic.

While many American women chafed at their social, spatial, and political limitations, some car makers began to fashion new wheels to preserve the dainty domain of Victorian decorum. Colonel Albert A. Pope, president of the Pope Manufacturing Company of Hartford, Connecticut, believed that “you can’t get people to sit over an explosion.” As he moved his company out of bicycle manufacturing and into the automobile business, he determined to concentrate not on noisy, smelly gasoline-powered cars, but instead, on clean, quiet electric vehicles. By 1897, the Pope Manufacturing Company had produced some five hundred electric cars.

While Pope pursued this entrepreneurial strategy, thousands of Americans proved him a bad prophet and purchased gasoline motorcars. In response to demand, Pope began to produce some gasoline cars, but the company remained committed to the idea that there was a natural market for slower, cleaner electrics. As Pope suggested in a 1903 advertisement for the Pope-Waverly electric model, “electrics . . . will appeal to any one interested in an absolutely noiseless, odorless, clean and stylish rig that is always ready and that, mile for mile, can be operated at less cost than any other type of motor car.” Lest this message escape those it was intended to attract, the text accompanied a picture of a delighted woman driver piloting a smiling female passenger.

Pitching electric cars to women represented a strategy that was at once expansive and limiting, both for automakers’ opportunities, and for women who wanted to be motorists. After all, in the infancy of the automobile industry, men like Pope had to unravel mysteries of design and production—What kinds of devices might make a carriage move without benefit of a horse? Would gasoline, steam, or electricity prove to be the most practical source of power? Might not all three have their disparate uses? How should such devices be manufactured? What materials should they be made of? How might they be distributed? Neither omniscient nor omnipotent, auto manufacturers generally produced individual vehicles on order and groped only haltingly toward perceiving a wider market.

The French and German automakers who pioneered the business in the late nineteenth century had produced luxury motorcars for the sporting rich, and at first, American manufacturers followed the European example in catering to the domestic carriage trade. As early as 1900, American socialites, male and female, vied with one another in devising ways of using the auto for entertainment. Wealthy men held races and rallies at various posh watering holes; women attended, and sometimes participated. Prominent women also developed their own automotive spectacles. They besieged Newport, Rhode Island, (where many of America’s wealthiest families built expensive vacation homes) in flower-decked car convoys, held drive-in dinner parties where they demanded curb service at fashionable Boston restaurants, or simply stepped from their elegant conveyances at the opera house door, dripping diamonds and pearls. In keeping with the tastes of their owners, expensive motorcars featured such “refinements” as cut-glass bud vases and built-in vanity cases.

These male and female motoring larks differed more in terms of style than substance; wealthy men and women shared a taste for luxury and leisure, as well as bracing adventure, in their motoring. Nevertheless, manufacturers tended to associate the qualities of comfort, convenience, and aesthetic appeal with women, while linking power, range, economy, and thrift with men. Women were presumed to be too weak, timid, and fastidious to want to drive noisy, smelly gasoline-powered cars. Thus at first, manufacturers, influenced by Victorian notions of masculinity and femininity, devised a kind of “separate spheres” ideology about automobiles: gas cars were for men, electric cars were for women.

The electric automobile had been around since the birth of the motor age, and its identification with women took hold early and tenaciously. Genevera Delphine Mudge of New York City, identified by one source as the first woman motorist in the United States, drove an electric in 1898, and one Miss Daisy Post also drove an electric vehicle as early as 1898. In 1900, the City Engineer of Chicago complained that many women drivers were not bothering to get licenses, and Horseless Age magazine, conflating all women drivers with those who drove electrics, noted that “so far only eight women have secured permits to operate electric vehicles, but . . . there are twenty-five to fifty women regularly running the machines through the city.”

Certainly some women who wanted the increased mobility that came with driving a car believed that gasoline vehicles, being powerful, complicated, fast, dirty, and capable of long-distance runs, belonged to men, while electric cars, being simple, comfortable, clean, and quiet, though somewhat short on power and restricted in range, better suited women. Electrics tended to be smaller and slower than gasoline-powered cars, and often were designed as enclosed vehicles. If electrics offered less automobility than gas cars, they offered greater mobility than horses, and more independence and flexibility than trolleys. Understandably, some women—most of them well-to-do—thus chose to drive electrics. In April of 1904, Motor magazine’s society columnist noted:

Mrs. James G. Blaine has been spending the last few weeks with her parents at Washington, and has been seen almost daily riding about in an electric runabout. The latter appears to be the most popular form of automobile for women, at any rate in the National Capital. . . . Indeed, judging from the number of motors that one sees driven by women on a fine afternoon, one would imagine that nearly every belle in Washington owned a machine.

Like Pope, other electric car manufacturers were quick to see women as a potential gold mine. In the years before World War I, articles on electric vehicles, or on women drivers, and advertisements for electrics in such publications as Motor and Country Life in America featured photographs of women driving, charging, and otherwise maintaining electrics, reflecting both a specific marketing strategy and a more diffuse cultural tendency to divide the world between masculine and feminine. Electric vehicle manufacturers including the Anderson, Woods, Baker, Borland, and Milburn companies featured women in their advertisements. Touting such virtues as luxury, beauty, ease of operation, and economy, manufacturers attempted to appeal to an affluent female clientele without alienating men who might wish to purchase an electric for their wives or daughters, or even for themselves. The Argo company advertised its 1912 model, a sporty low-slung electric vehicle, as “a woman’s car that any man is proud to drive.” The Anderson Electric Car Company invited men to purchase its Detroit model “for your bride-to-be—or your bride of many Junes ago. . . . No other bridal present means so much—expresses so perfectly all that you want to say. . . . the most considerate choice for her permanent happiness, comfort, luxury, safety.” The Detroit Electric was said to be not only “the last word in luxury and beauty, as well as efficiency,” but also a boon to feminine comeliness:

To the well-bred woman—the Detroit Electric has a particular appeal. In it she can preserve her toilet immaculate, her coiffure intact.

She can drive it with all desired privacy, yet safely—in constant touch with traffic conditions all about her.

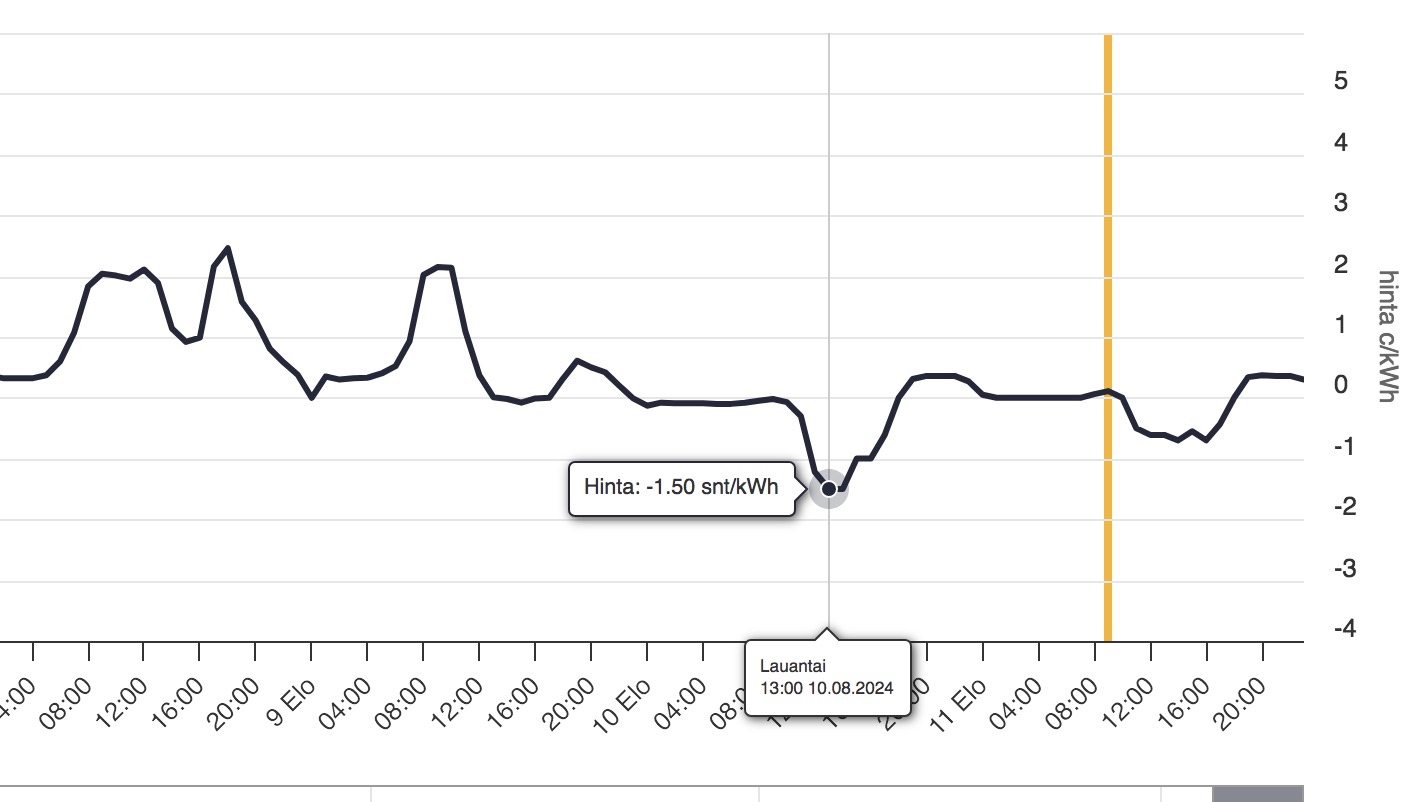

However much manufacturers trumpeted the appealing qualities of electrics, automobiles powered by electric batteries had serious disadvantages compared to gas-powered vehicles. They were generally more expensive to manufacture, had limited range (averaging twenty to fifty miles per charge), and were too heavy to climb hills or run at high speeds. Inventor Thomas Edison promised that he would develop a long-distance electric storage battery, but his efforts in this regard proved fruitless. By 1908, even some of those who applauded the use of electrics admitted their limitations. Writer Herbert H. Rice noted that despite improvements in charging technology and vehicle design, “there are not apparent any great opportunities for extraordinary changes unless in the battery.” Rice advised the motoring public to give up hoping for a battery that would go one hundred miles on a single charge (a hope which, he admitted, had caused electric sales to suffer) since “not one in one hundred users requires a service extending beyond thirty-five miles, while in the majority of cases the odometer would record less than fifteen miles for the day’s errands.”

This acknowledgment of the electric auto’s problems suggests that its association with women was at once a symptom of, and an attempted cure for, its competitive disadvantages. The electric’s circumscribed mobility seemed adequate to those who assumed that “the electric is the vehicle of the home,” adequate, that is, for homemakers who did not expect to take long trips, or frequent trips, or to get stuck in traffic jams. Playing on the domestic theme, the General Electric Company asserted, “any woman can charge her own electric with a G-E Rectifier,” advertising with a photograph of a woman charging her car, using a machine that occupied most of one wall of the family garage. Declaring that “there are no tiresome trips to a public garage, no waiting—the car is always at home, ready when you are,” General Electric implied that using the rectifier would relieve the woman motorist of such inconveniences as often accompanied having to leave home.

At times the electric car and its purportedly female clientele seemed entwined, as the electric’s advocates used a Victorian language of gender to talk about cars. Country Life in America writer Phil M. Riley combated the criticism that “electric power is weak,” by asserting, “It is important with an electric not to waste power needlessly, that is all.” Riley assured his readers that “the proper sphere of the electric vehicle is not in competition with the gasolene [sic] touring car.” Just as conservative commentators admonished women to forego high-powered business and political activity and conserve their energy for domestic tasks, so, Riley said, the electric vehicle might fulfill its mission as “an ever-ready runabout for daily use,” leaving extended travel and fast driving to men in gas-powered cars. Moreover, both Rice and Riley chose to refer to the electric vehicle’s venue of operation as a “sphere.” Victorian Americans commonly repre sented women’s and men’s respective social roles as “separate spheres.” This simple visual image often served as a shorthand description of complex relations not only between individuals of different biological sexes, but between feminine and masculine attributes (including passivity and activity), private and public life, household and workplace, homemaking and paid work, cul ture and politics. The automobile might be novel, but it could not escape entanglement in a web of meaning spun with threads of masculinity and femininity.